In Room To Bloom Classroom we are doing a Tiny Tot Theater Production

Even though out TTT theater productions are not Kindermusik, we are covering a great deal of musical details for these students.

One of these is "Pantomime" a theater definition of creating a scene without using words or objects ... make believe your peeling a banana or reading a book. Frank Leto helps us with his famous song

"Pantomime.. "

We are working with Stop and Go with yet another Frank Leto song called

"Tip Toe"

We are using words like finding your Mark on stage... and cues with hands for off stage communication.

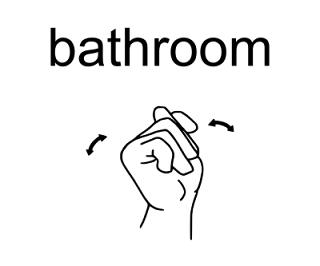

Speaking of Communication.. I am now starting to use ASL for teaching music to the students at Room

to Bloom as well..

This school so rocks !

Call Miss Ashley at Room To Bloom if your interested in her programs there.

There is also a great Kindergarten.

We have created some fun songs using the dynamics of loud and soft .

As we move along in class we will be experiencing more of the aspects of dynamics . Even though your children at Room to Bloom with not be getting all of the below.. they will be bringing the natural rhythm of music into their daily lives as well as learning a few fun facts about music drama and art..

Tra La La....

Miss Mana

Read up on this user friendly definition of Dynamics brought to you by Wikipedia . !

In

music,

dynamics normally refers to the

volume of a

sound or

note, but can also refer to every aspect of the execution of a given piece, either stylistic (staccato, legato etc.) or functional (velocity). The term is also applied to the written or printed

musical notation used to indicate dynamics. Dynamics are relative and do not indicate specific volume levels.

[edit]Relative loudness

Teacher. "And what does

ƒƒ mean?"

Pupil (after mature deliberation). "Fump-Fump."

Cartoon from

Punch magazine October 6, 1920

The two basic dynamic indications in music are:

- p or piano, meaning "soft".

- ƒ or forte, meaning "loud".

More subtle degrees of loudness or softness are indicated by:

- mp, standing for mezzo-piano, meaning "moderately soft".

- mƒ, standing for mezzo-forte, meaning "moderately loud".

Beyond f and p, there are also

- pp, standing for "pianissimo", and meaning "very soft",

- ƒƒ, standing for "fortissimo", and meaning "very loud",

To indicate an even softer dynamic than pianissimo,

ppp is marked, with the reading

pianissimo possibile ("softest possible"). The same is done on the loud side of the scale, with

ƒƒƒ being

fortissimo possibile ("loudest possible").

[2][3]

Note Velocity is a

MIDI measurement of the speed with which the key goes from its rest position to completely depressed, with 127, the largest value in a 7-bit number, being instantaneous, and meaning as loud as possible.

Few pieces contain dynamic designations with more than three

ƒ's (sometimes called "fortondoando") or

p's. In

Holst's

The Planets,

ƒƒƒƒ occurs twice in Mars and once in Uranus often punctuated by organ and

ƒƒƒ occurs several times throughout the work. It also appears in

Heitor Villa-Lobos'

Bachianas Brasileiras No. 4 (Prelude). The

Norman Dello Joio Suite for Piano ends with a crescendo to a

ƒƒƒƒ, and

Tchaikovsky indicated a bassoon solo

pppppp in his

Pathétique Symphonyand

ƒƒƒƒ in passages of his

1812 Overture and the 2nd movement of his

Fifth Symphony.

Igor Stravinsky used

ƒƒƒƒ at the end of the finale of the

Firebird Suite.

ƒƒƒƒ is also found in a prelude by

Rachmaninoff, op.3-2.

Shostakovich even went as loud as

ƒƒƒƒƒ in his

fourth symphony.

Gustav Mahler, in the third movement of his

Seventh Symphony, gives the celli and basses a marking of

ƒƒƒƒƒ, along with a footnote directing '

pluck so hard that the strings hit the wood.' On another extreme,

Carl Nielsen, in the second movement of his

Symphony No. 5, marked a passage for woodwinds a diminuendo to

ppppp. Another more extreme dynamic is in

György Ligeti's

Études No. 13 (

Devil's Staircase), which has at one point a

ƒƒƒƒƒƒ and progresses to a

ƒƒƒƒƒƒƒƒ. In Ligeti's

Études No. 9, he uses

pppppppp. In the baritone passage

Era la notte from his opera

Otello,

Verdi uses

pppp. Steane (1971) and others suggest that such markings are in reality a strong reminder to less than subtle singers to at least sing softly rather than an instruction to the singer actually to attempt a

pppp. Usually, the extra

f's or

'ps written reinforce either

ffor

pp, and are usually only for dramatic effect.

In music for marching band, passages louder than ƒƒƒ are sometimes colloquially referred to by descriptive terms such as "blastissimo".

Dynamic indications are relative, not absolute.

mp does not indicate an exact level of volume, it merely indicates that music in a passage so marked should be a little louder than

p and a little quieter than

mf. Interpretations of dynamic levels are left mostly to the performer; in the

Barber Piano Nocturne, a phrase beginning

ppis followed by a diminuendo leading to a

mp marking. Another instance of performer's discretion in this piece occurs when the left hand is shown to crescendo to a

ƒ, and then immediately after marked

p while the right hand plays the melody

ƒ. It has been speculated that this is used simply to remind the performer to keep the melody louder than the harmonic line in the left hand. In some

music notation programs, there are default

MIDI key velocity values associated with these indications, but more sophisticated programs allow users to change these as needed.

[edit]Sudden changes

Sudden changes in dynamics are notated by an

s prefixing the new dynamic notation, and the prefix is called

subito.

Subito is Italian as are most other dynamic notations, and translates into "suddenly".

[4] It is usually used along with

forzando (Italian for "forcing"), to make

subito forzando, or what most people refer to as just

sforzando (

sfz). Other common uses of subito are before a regular dynamic notation, like in

spp,

sf, or

sff.

Subito forzando (sfz) notation

Sforzando (or sforzato), indicates a forceful, sudden accent and is abbreviated as sƒz. Regular forzando (fz) indicates a forceful note, but with a slightly less sudden accent.

The

fortepiano notation

ƒp (or

subito fortepiano;

sƒp) indicates a

forte followed immediately by

piano. This notation is usually used to give an unusual strong (and sudden if

subito) accent.

One particularly noteworthy use of

forzando is in the second movement of

Joseph Haydn's

Surprise Symphony.

Rinforzando,

rƒz (literally "reinforcing") indicates that several notes, or a short phrase, are to be emphasized.

Rinforte (

rƒ) is also available.

[edit]Gradual changes

In addition, two words are used to show gradual changes in volume. These words are crescendo and diminuendo.

Crescendo, sometimes abbreviated to

cresc., literally translates "to become gradually stronger", but is interpreted as louder gradually, and the correct Italian

diminuendo -- abbreviated as

dim., means "to become gradually softer". The alternate and made-up English word

decrescendo, abbreviated to

decresc., also means "to get gradually softer". Signs sometimes referred to as "hairpins"

[5] are also used to stand for these words (See image). If the lines are joined at the left, then the indication is to get louder; if they join at the right, the indication is to get softer. The following notation indicates music starting moderately loud, then becoming gradually louder and then gradually quieter.

Hairpins are usually written below the

staff, but are sometimes found above, especially in music for

singers or in music with multiple melody lines being played by a single performer. They tend to be used for dynamic changes over a relatively short space of time, while

cresc.,

decresc. and

dim. are generally used for dynamic changes over a longer period. For long stretches, dashes are used to extend the words so that it is clear over what time the event should occur. It is not necessary to draw dynamic marks over more than a few bars, whereas word directions can remain in force for pages if necessary.

For quicker changes in dynamics,

cresc. molto and

dim. molto are often used, where the

molto means

much. Similarly, for slow changes

cresc. poco a poco and

dim. poco a poco are used, where

poco a poco translates to

little by little.

[6]

[edit]Words/phrases indicating changes of dynamics

(In Italian unless otherwise indicated)

- al niente: to nothing; fade to silence. Sometimes written as "

n"

n"

- calando: becoming smaller

- calmando: become calm

- crescendo: becoming stronger

- dal niente: from nothing; out of silence

- decrescendo or diminuendo: becoming softer

- fortepiano: loud and accented and then immediately soft

- fortissimo piano: very loud and then immediately soft

- in rilievo: in relief (French en dehors: outwards); indicates that a particular instrument or part is to play louder than the others so as to stand out over the ensemble. In the circle of Arnold Schoenberg, this expression had been replaced by the letter "H" (for German, "Hauptstimme"), with an added horizontal line at the letter's top, pointing to the right, the end of this passage to be marked by the symbol "┐ ".

- perdendo or perdendosi: losing volume, fading into nothing, dying away

- mezzoforte piano: moderately strong and then immediately soft

- morendo: dying away (may also indicate a tempo change)

- marcato: stressed, pronounced

- pianoforte: soft and then immediately strong

- sforzando piano: with marked and sudden emphasis, then immediately soft

- sotto voce: in an undertone (whispered or unvoiced)[7]

- smorzando: dying away

[edit]History

The

Renaissance composer Giovanni Gabrieli was one of the first to indicate dynamics in

music notation, but dynamics were used sparingly by composers until the late 18th century.

Bach used some dynamic terms, including

forte,

piano,

più piano, and

pianissimo (although written out as full words), and in some cases it may be that

ppp was considered to mean

pianissimo in this period.

The fact that the

harpsichord could play only "terraced" dynamics (either loud or soft, but not in between), and the fact that composers of the period did not mark gradations of dynamics in their scores, has led to the "somewhat misleading suggestion that baroque dynamics are 'terraced dynamics'," writes Robert Donington.

[8] In fact, baroque musicians constantly varied dynamics. "Light and shade must be constantly introduced... by the incessant interchange of loud and soft," wrote

Johann Joachim Quantz in 1752.

[9] In addition to this, the harpsichord in fact becomes louder or softer depending on the thickness of the musical texture (four notes are louder than two). This allowed composers such as Bach to build dynamics directly into their compositions, without the need for notation.

In the Romantic period, composers greatly expanded the vocabulary for describing dynamic changes in their scores. Where Haydn and Mozart specified six levels (

pp to

ff), Beethoven used also

ppp and

fff(the latter less frequently), and Brahms used a range of terms to describe the dynamics he wanted. In the slow movement of the trio for violin, waldhorn and piano (Opus 40), he uses the expressions

ppp,

molto piano, and

quasi niente to express different qualities of quiet.

[edit]See also